Where do I start? My fingers quiver as I take on typing something about Manto. Those who have read him will understand why. Those who haven’t, I hope this will lead you to pick up his work. That is my simple mission here.

How do you tackle a fearless writer? How do you cut out all the frills in your writing to take on a no-nonsense, honest form of penmanship that often leaves you breathless?

To write on Manto is to question the honesty of your own writing. To read Manto is to educate yourself.

There is no way to go other than grabbing the bull by its horns.

Born in 1912 in Ludhiana, India, he died in 1955 in Lahore in Punjab in Western Pakistan. His nationality lists as Indian (1912-1948) and Pakistani (1948-1955). This clear distinction between the rest of his life and the last seven years is where we find Manto in all his agony. His writing is said to have taken a definitive turn of form and become ‘darker’ post-partition.

Understanding Manto’s anguish is challenging without the historical context. Much like Albert Camus, Manto’s life story and many of those he wrote are inseparable from his country of birth and the dramatic turn of events in the middle of the 20th century.

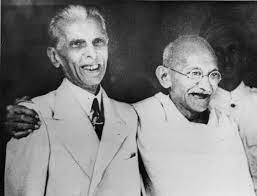

Many religions had taken root and grown from the ground up on Indian soil. Yet, once India became a colonial economy under the British East India Company (which gained a foothold in India in the early 17th century and subsequently came under the British crown in 1858), religion soon became the center of the British divide-and-rule strategy in India. The Indian independence movement ultimately succeeded with the ouster of the British in 1947 – freedom, however, came at a bloody price.

“In 1947, the British Indian Empire was partitioned into two independent dominions, a Hindu-majority Dominion of India and a Muslim-majority Dominion of Pakistan, amid large-scale loss of life and an unprecedented migration.” – Wikipedia.

Overnight, millions of people – the Hindus of ‘Pakistan’ and the Muslims of ‘India’ crossed over to the other side. It was one of the largest migrations in human history [UNHCR estimates that 20 million Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims were displaced during the Partition of India, the largest mass migration in human history]. Unthinkable violence with widespread massacres, rape, looting, and kidnapping accompanied India’s separation. Blood flowed on the streets of the Panjab and North India. Trains came from across the borders loaded with dead bodies; its passengers hacked down along the way.

All this came at the added human cost of families separated forever in the two countries and people going missing, many never to be found again. Worried about the safety of his daughters, Manto was one of those who had to undertake this heartbreaking journey across and found himself disoriented in a ‘new’ country.

Taking a walk through the lanes of Lahore and trying to make sense of a known city in a new country, he writes, with his trademark wit, and in his characteristic detached manner,

“It was a strange season and a strange morning. Almost all the shops were shut. A halwai1 was open. I thought a glass of lassi2 would be refreshing. In the shop I noticed that the fan was on, but turned away from both customers and the owner. I was curious and asked why it was so. The owner glared at me and said: ‘Can’t you see?’. I looked. The fan was pointed in the direction of a poster of our great leader, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. I shouted, ‘Pakistan zindabad!’ and left without the lassi.”

–A stroll through the new Pakistan. Why I write? (PATEL, 2014, p. 84)

He documented this reality of the partition days in his essays and presented this reality through his prose in many short stories after moving to Lahore.

Multiple writers have documented those traumatic days of forced separation. No one has achieved this with the depth of observation, objective distance, and clarity than Saadat Hasan. Manto, who loved Bombay, never quite got over the fissures created in his land.

In his introduction to a volume of Manto’s essays (‘Why I Write?’ edited and translated from Urdu to English), journalist and editor, Aakar Patel, says:

“Saadat Hasan Manto was an Indian trapped in Pakistan. His identity didn’t come from religion, and it came only partially from geography …”

(PATEL, 2014, p. vii)

The split was not just literal; it was a split that forced Manto to think about the idea of a nation and what constituted ‘belonging.’ He pondered over questions about the art, the literature, and the joint musical traditions of erstwhile India and who these would belong to in this new geographical reality.

On finding a statue missing in a familiar town square, someone tells him that it had been taken by those who ‘owned’ it. He surmises, ” (…) even statues were now refugees. There might come a day when corpses would also be dug up and moved across the border.” ‘A Stroll through the new Pakistan. Why I write? (PATEL, 2014, p. 88)

No one wrote about this crazy idea of splitting a civilization into two countries based on a trumped-up religious divide more fervently, feverishly, doggedly, and with more impact than Saadat Manto. In his own words, “I saw much of this savagery myself but kept my feelings and anguish within.” One can argue it drove him to his grave for he died, aged 42, in 1955 in Lahore of cirrhosis of the liver caused by alcohol addiction (much like the master storyteller, O’Henry, who died a half-century earlier, almost penniless, and of the exact cause at the age of 47).

It was hard to pick just one of Manto’s stories on the partition, inevitably doing injustice to a few others. Hard-pressed to do this, I ultimately chose ‘Toba Tek Singh,’ his searing satirical piece on the partition and its madness. I will take on another one, ‘Khol Do’ (Open it!), in a subsequent post.

Toba Tek Singh

A couple of years post-partition, officials from both countries have decided that Hindu and Muslim ‘lunatics’ in asylums should be ‘exchanged’. Since most Hindu and Sikh families have migrated already, the attention shifts to an asylum in Lahore whose inmates belonging to these two communities must now move to India.

When the inmates hear of this imminent transfer, all kinds of conjecture arise. There is confusion and angst, and panic. No one knows where they were, or where India was, or where Pakistan will find itself.

“If they were in India, then where on earth was Pakistan? And if they were in Pakistan, then how come that until only the other day it was in India?”

One would imagine such confusion residing in the heart of every ‘sane’ Indian when the news of imminent Partition might have trickled in.

One inmate got so worked up by the confusion that he climbed up a tree in the yard and, after every attempt at getting him down failed, said,

“I wish to live neither in India nor in Pakistan. I wish to live in the tree.”

A blazing satire on institutional and institutionalized madness, Manto explores where the absolute lunacy lies – ‘inside’ or ‘outside.’ Are the ‘officials’ making these decisions sane?

Bishan Singh or ‘Toba Tek Singh’ – named thus after the village in Punjab that he hails from, is another inmate at the asylum. On the designated day of the exchange, the ‘mad’ people are taken to Wagha.

“On a cold winter evening, buses full of Hindu and Sikh lunatics, accompanied by armed police and officials, began moving towards Wagha, the dividing line between India and Pakistan.”

On reaching there, Bishan Singh asks an official which side of the border Toba Tek Singh was. One official tells him it will be in Pakistan. Hearing this, Bishan Singh tries to run and refuses to budge across the border over to India. He stays there, standing – on no man’s land – overnight, his legs swollen. Early the following day, he collapses and dies right there – on land which belongs to nobody and has no name.

“There behind barbed wire, on one side, lay India and behind more barbed wire, on the other side, lay Pakistan. In between, on a bit of earth which had no name, lay Toba Tek Singh.”

Much as his prose is ingenious and controlled, I find Saadat Hasan vivid in his non-fiction, his essays and anecdotes, and in his chronicles of the partition. They provide us with the mise-en-scène for the intense stories.

Reality trumps fiction in Manto’s essays in ‘Why I write?’. There are grim moments as there is much laughter at his many anecdotes.

His essays on the partition documented in this book give us a sense of why Manto is timeless. In the piece, ‘Hindustan ko leaderon se bachao‘ (Save India from its leaders), he says,

“These people – ‘leaders’ – see religion and politics as some lame, crippled man. They peddle him around to beg for money. They shoulder his corpse and appeal to those who will believe anything said from high on up … When these leaders shed tears and wail, “Mazhab khatre mein hai” (Religion is in danger), it is all rubbish … Save India from its leaders, who are poisoning our atmosphere (…).”

Bells are ringing everywhere in current-day India. As we sit up and take notice, I wonder how a man who prophetically, and in Orwellian fashion, warned us of the future we are now living could have gone ignored for so long. In another essay, ‘The guilty men of Bombay‘, he is prescient while referring to the partition riots.

” … A few months after my coming, Hindus and Muslims began fighting, and kept fighting. The cause was the same as it always is — mandir, masjid … you know it well.”

Those of us who have lived in India the last few decades and lived the Ayodhya riots, the squabbling over the Ram mandir, the Gujarat riots, and the attempt by our ‘leaders’ to dig up the corpse of religion further and gain political ground by cementing the idea of a ‘Hindu Rashtra’ (Hindu nation) – yes! – we do know it well!

Manto, once again on the money, talking about those responsible for the riots in Bombay:

“These are people who want to take India to a state of barbarism. They want to spread insecurity through fear and carnage, so that their interests remain secure. (…)”

‘The Guilty men of Bombay’: Why I write?

Fast forward almost 75 years to 2020, the Indian government’s attempt to push through a controversial citizenship amendment law, the protests all over the country against this law, and the communal riots in the wake of these protests in Delhi and the above words by Manto come alive once again. Timeless.

Just two years ago, my husband and I had discussed possible ways to protect our two Muslim home staff should the flames from the Delhi riots reach Bangalore. One way of keeping them safe during any violence was to perhaps prevent the women from wearing the burqua should things get out of hand.

Manto talks about religion’s badges that could spell the difference between a passport to safety or a death sentence during the riots.

“In earlier riots, when we left home we would carry two caps. A hindu topi and a Rumi topi. When passing through a Muslim mohalla, we would put on the Rumi topi and when walking through a Hindu mohalla, the Hindu topi. In this riot, we also bought Gandhi topis. These we kept in our pockets to be pulled out whenever needed. Religion used to be felt in the heart, but now, in the new Bombay, it must be worn on the head.”

‘Bombay in the riots’: Why I write?

Manto had witnessed the chaos, confusion, and utter bewilderment of the asylum inmates depicted in Toba Tek Singh. It was the anarchy in Bombay during Partition. He says,

“When India was partitioned, I was in Bombay (…). And I saw the chaos that came to the city. (…) Those were strange days. There was chaos, mayhem, panic everywhere and from the womb of this anarchy were born two nations. (…)”

‘Bombay during Partition’: Why I write?

Even in describing the anarchy that partition unleashed and the tumult that ensued in his life post-partition when left Bombay under duress and headed for Lahore, Manto keeps his humor intact. When he is sent a notice by the Pakistani authorities saying he was an ‘unwanted person’ and asking him to vacate the house allotted to him as refugee property, he says,

“If I am now declared an ‘unwanted person,’ the government perhaps also reserves the right to declare me a rat and exterminate me. Anyway, for now I’m safe here in Pakistan.”

Manto took innumerable such digs and potshots at the establishment in Toba Tek Singh, recognizing the whole affair of the partition also as a kind of comedy of errors, a madman’s playhouse, a circus almost.

“Since the start of this India-Pakistan caboodle …” he says in Toba Tek Singh while making the setting of the exchange of ‘lunatics’ almost comical, dark yet funny, almost laughable and yet foreboding and ominous.

[Complement this reading with stories by Manto’s contemporaries across continents. Albert Camus and his anguish at the violent circumstances during Algeria’s fight for independence and Tadeusz Borowski’s Auschwitz stories.]

1. Halwai: A local confectioner

2. Lassi: A cold sweet or savory drink made with yogurt and water

Bibliography

- Nast, Condé. “The Mutual Genocide of Indian Partition.” The New Yorker, June 21, 2015. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/06/29/the-great-divide-books-dalrymple.

- PATEL, AAKAR. Why i Write: Essays by Saadat Hasan Manto. Tranquebar, 2014.